Making the Most of Job Interviews

August 19, 2022Leveling Up Your Open Enrollment Game: Tips for Success

September 13, 2022Making the Most of Job Interviews

August 19, 2022Leveling Up Your Open Enrollment Game: Tips for Success

September 13, 2022- Hiring scams are proliferating, stealing more than $68 million through fake opportunities in Q1 2022 alone.

- Recently scammers used LinkedIn to pose as recruiters working for Mineral, relying on connections with legitimate employees to lend them credibility so they could prey on unsuspecting victims.

- As an employer, you can’t prevent these scams, but there are several steps you can take to protect your company and potential victims

- Report any instance of fraudulent hiring practices to the correct regulatory agency or law enforcement organization.

According to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center, over 16,000 employment and hiring scams were reported in 2020. These scams resulted in $59 million in losses for employers and employees. This trend has only continued in the increasingly digital world as scammers stole $68 million through fake business and job opportunity scams in the first quarter of 2022 alone.

Scammers hit home at Mineral

LinkedIn has created a trusted community where a request to connect from a stranger isn’t creepy — it’s called networking. And it’s exactly what makes this platform such an attractive hunting ground for scammers.

In the first six months of 2021 LinkedIn detected and removed more than 15 million fake accounts. Yet scammers persist in breaking through the platform’s defenses because they know community trust lowers member defenses, which makes posing as a sheep in wolf’s clothing lucrative for them.

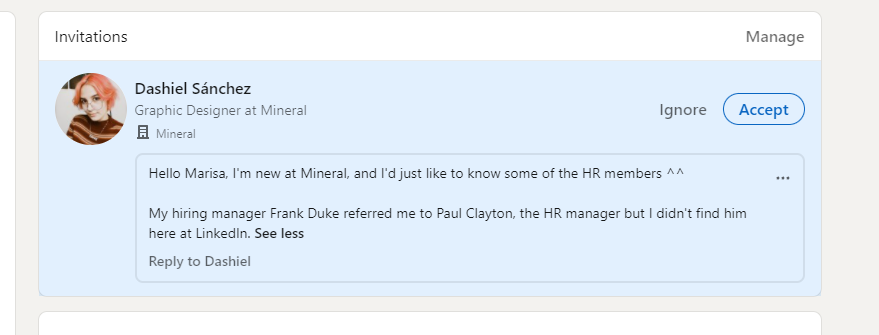

Mineral became an unwilling accomplice in a LinkedIn hiring scam a few months ago, when I was recruiting for a graphic designer. My first clue came in the form of a Slack from a concerned colleague. She said “Dashiel Sanchez,” a Mineral graphic designer, had requested to connect with her on LinkedIn. Since the graphic designers report to me, I knew immediately this was a fake profile.

Within days, Mineral’s HR team forwarded emails to me from concerned job seekers, asking if the recruitment messages they’d received about our graphic designer role were real. We had to act fast to protect unsuspecting victims and prevent any damage to our reputation as an employer.

I put on my investigative hat and got to work sniffing out this mystery. I figured out what was happening and worked with my social media, web, and HR teams to identify steps to immediately blunt the impact of the scams. Here’s what we learned, how we fought back, and what you can do to protect your organization.

What did the scammers do?

First, the scammers created multiple fake Mineral employee profiles on LinkedIn. Like “Dashiel Sanchez,” these fake employees invited real Mineral employees to connect.

They also created fake email addresses using a domain name that looked real: trustmineral.us (our real domain is trustmineral.com).

Next, they scraped the graphic designer job posting from our careers page, edited the description to turn it into an hourly position, exaggerated our benefits, and made it clear payment would be through bank transfers.

They turned all this into a Mineral-branded PDF that looked official, even to me. The PDF included instructions to install software on their computer in order to communicate with the recruiter, Frank Duke.

Then they targeted victims using LinkedIn in two different ways. One, they targeted potential candidates via email with a recruitment offer and the PDF; and two, they netted unsuspecting job candidates by posting the job on LinkedIn as Mineral.

Finally, the scammers created various personas to add credibility and reflect the community nature of LinkedIn.

In the following email, a concerned victim (name redacted), refers to a message from Paul Clayton.

Paul Clayton, HR manager. Frank Duke, hiring manager. Dashiel Sanchez, graphic designer (the role I was filling). These scammers took the time not only to create fake profiles, but interconnected accounts with job titles that could vouch for each other. It was a layered scheme designed to plausibly pass a basic vetting by a skeptical candidate.

Here’s how we fended off the hiring scammers

- We asked employees to ignore suspicious LinkedIn requests

We had to take away the scammer’s veneer of credibility. That meant asking employees to make sure a colleague’s request to connect on LinkedIn was real. This isn’t foolproof. Some co-workers don’t have updated profiles or may have different last names on LinkedIn. But verifying someone works with you can be as easy as seeing if they have an active email or Slack account, or if they show up in a company HRIS system. Unfortunately, verifying if someone is a former employee is harder and would require HR assistance.

- We reported suspicious activity and posted warnings on LinkedIn

- We reported the fake accounts to LinkedIn and asked them to remove them. It took about two weeks, but it worked. In fact, one job seeker’s inability to find Paul Clayton’s profile on LinkedIn led them to become suspicious and report the scam to us.

- We tried to see if LinkedIn had a verification process that would require an employee to prove they worked for Mineral. Good news: they do have a verification process. Bad news: it only serves to enable employees to access the “My Company” tab or job posts. Anyone can still add your company’s account to their work experience. Unfortunately, this verification process is useless against scammers.

- We edited the graphic designer LinkedIn posting to include a warning about scammers.

- Last, but not least, we pinned a warning message to Mineral’s company page.

- We warned job seekers on our website’s Careers page

- We added a warning to every single job posting.

- We updated our website’s Careers page to include the same warning.

- We used our chatbot to not only warn job seekers but also advise them that any interaction from a Mineral recruiter would be from an email with the trustmineral.com domain.

- We shared our HR team’s contact information to make it easy for candidates to report any concerns.

Were the scammers successful?

Five victims reported suspicious incidents to Mineral. Three of them avoided the scam and merely passed along the details to us. The two that interviewed for the fake role revealed two different scams: scheming to gain bank account access and defrauding victims using phony checks.

In the case of the phony checks, the victim was told to expect a check to purchase new software and a computer:

This request sounds typical, right? The company should pay for equipment associated with a new job. And it’s not an odd request given it’s clearly listed in the PDF:

However, in this type of scam, the victim is directed to purchase equipment from suppliers run by the scammers (“These would be delivered to your address from our vendors”). They mail the victim a bogus check to cover the purchase, betting on the fact that by the time the check bounces, the victim will have already made a transaction. If so, by the time the bank negates the deposit of the phony check, the victim will have lined the pocket of the scammer through their purchase with nothing to show for it. The scammer cashes in and moves on.

Thankfully, this victim’s bank detected the check as fraudulent before she could get swindled. We also responded to her email quickly enough to stop her from submitting her W2 to the scammer.

The scammers eventually gave up. But why did they target Mineral in the first place?

For several weeks, new fake profiles kept popping up almost as fast as we could get them removed. But once we put defensive measures in place, the scammers moved on. Afterward, I couldn’t help but wonder: what attracted hiring scammers to my job posting?

Mineral had tons of open positions posted at the same time as mine. But they were different in the sense that they couldn’t also be construed as hourly positions. I was hiring a graphic designer, a role often associated with an hourly rate. It could reasonably require a simple job screening and be paid through wire transfer. On the other hand, scammers would be challenged to approach candidates for a Director of Customer Experience role and expect to come across as legit.

What can you do to protect your company from hiring scams?

Notice I didn’t ask, “What can you do to prevent your company from being targeted by hiring scams?” Because there’s nothing you can do. Scammers are clever, with constantly shifting tactics. Unless victims alert you, you’ll never know there’s a scam involving your company. However, there are steps you can take to protect your organization:

Report and Flag Scammers

Many organizations are as interested as your business is in removing hiring scams when they are spotted. Most job sites work to ensure authentic opportunities by employing verification protocols, but they also offer options for employers to flag suspicious or fraudulent postings.

Additionally, as whenever any crime is afoot, law enforcement would like to hear about it. The Federal Trade Commission, the Better Business Bureau, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation offer online resource centers to submit these reports. You can report suspicious postings or emails using these links:

- Internet Crime Complaint Center

- Better Business Bureau

- Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Federal Trade Commission

- Google’s Report Phishing Resource Center

Spotting Hiring Scams Checklist

If your business is hiring, it’s important to search job boards for your posting and ensure no duplicates are listed. Some ways giveaway signs to train you or your staff on spotting these fraudulent listings include:

- Spelling or other grammar mistakes

- Listing third-party contact information, such as the wrong email

- Heightened sense of urgency

- Vague job descriptions

- Inaccurate description of the company

- Requiring payments (self-purchase of computer and software)

- Requests for personal banking or tax ID information

If you spot potential errors like these, act quickly and report them to your HR representative.

As a small business, here are some other things you can do to protect yourself against fraudulent hiring schemes:

- Publicize your hiring process on your website, job postings, and social media accounts. That way, job seekers know what to expect, which in turn makes it easier for them to detect fraud.

- Incorporate warnings to job seekers about scams into your recruitment messages and job postings.

- Provide employees with regular training on social media and internet safety practices.

- Provide official resources to staff on how to safely recruit talent to your organization.

Summing up

Your company has no control over how its name or job postings are used in these hiring scams. But that doesn’t let you off the hook. You may not stand to lose money with this type of scam, but you do risk losing your reputation as an employer.

So don’t stand by and let scammers victimize job applicants. There is no route off-limits to fraudsters and no area they won’t go to try and steal information from businesses and candidates. As their methods mature, you’ll need to keep learning and employing new strategies to protect your company and potential victims.

Scammers are counting on you being reactive, not proactive. Educate your employees about fake LinkedIn profiles. Caution job seekers to be vigilant. I encourage you to use the lessons and steps we took at Mineral to help your company stay a few steps ahead of scammers.

The post How Mineral Put the Kibosh on Hiring Scams appeared first on Mineral.